An Insider’s Look at Three Unique Artists

By Sabina Dana Plasse & Jennifer Walton

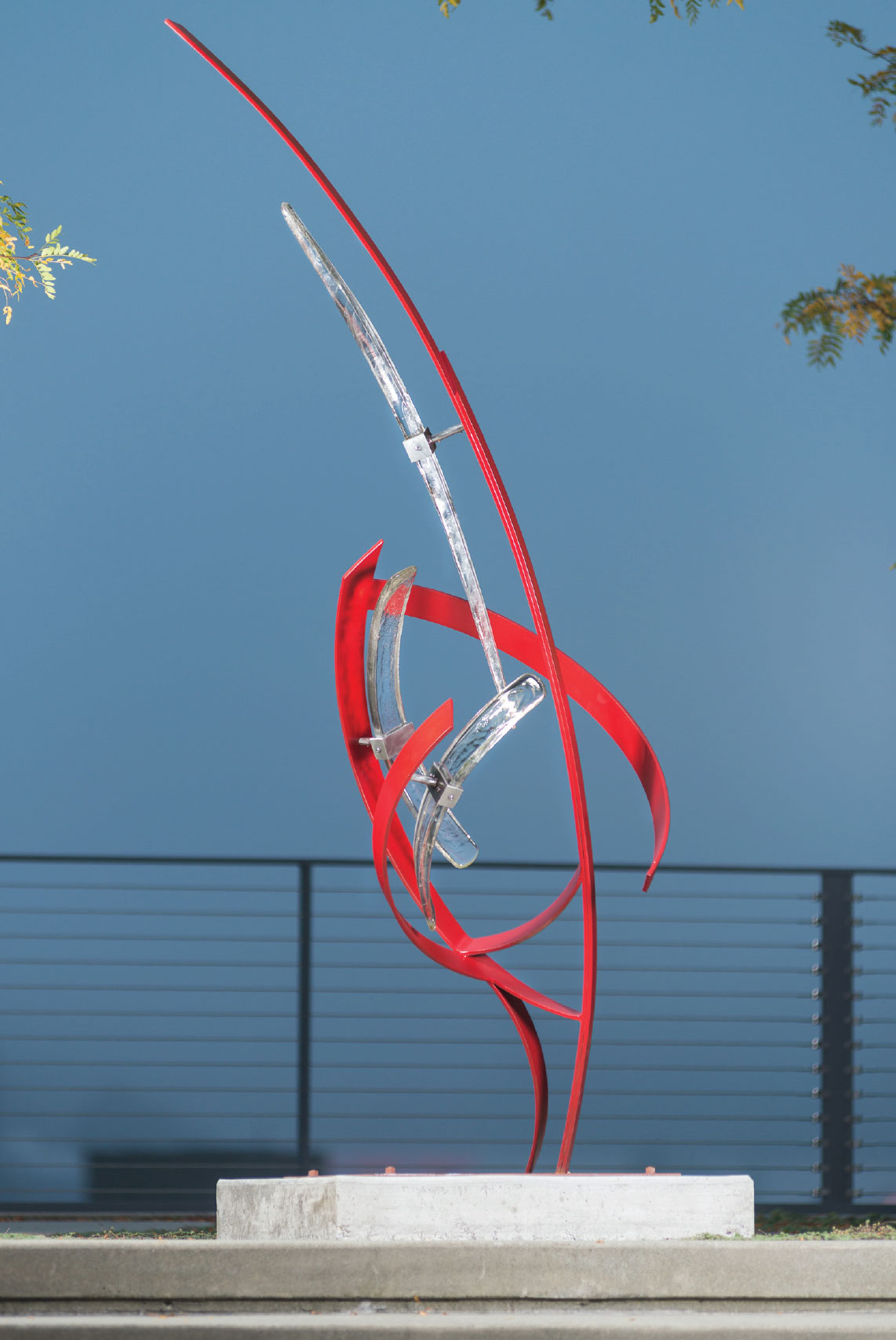

Ascent; 94”x 36”x 36” mild steel, glass. Ascent was commissioned by the city of Bellevue’s Bi-Annual Bellwether Exhibition in 2014 and on display at City Hall. In 2016-2017 it was on display at Palm Desert’s El Paseo exhibition.

As an artist community on the rise, Bend has a prominent connection to the West and Northwest. With the vast Oregon landscape and the mighty Deschutes River, along with majestic views of the Three Sisters, it’s no wonder that artists are inspired to be in Bend. In this issue of Western Home Journal, we feature the work of a new artist, Miguel Edwards, who migrated from Seattle, Washington, even though his roots are in New Mexico, and who now makes his home in Bend. Edwards is a sculptor whose steel art is inspiring and imaginative. With a history and career as a photographer, Edwards’ work and process as a sculptor is something remarkable to behold. Along with Edwards, we also feature the work of George Gulli. Gulli’s craftsmanship in his original totem pole carvings has a unique connection to collectors and art lovers who seek the rare, sublime, or ethereal level of art and heritage. In addition, we also feature the ledger artist Terrance Guardipee. Guardipee offers his own historic lesson on Native American culture with a look to the future from his ancestral roots. Explore Western fine art throughout this issue of Western Home Journal as another element to discovering or enhancing your dream home and surroundings in Oregon. As you flip the pages of Western Home Journal, discover your own appreciation for Northwest, Western, and Native American art, influences, and antiquities.

Sculptor Miguel Edwards:

Finds His Space in Bend

The Future is Liquid, a three-person exhibition at Space Gallery in Denver, with Michael Hedges and Monroe Hodder. Left to Right, Wing Raven 78”x 36”x 41” mild steel, Magpie Moon 73”x 30”x 32” mild steel, Wing Raven 77”x 42”x 36” mild steel, Elephant Dreams 69”x 37”x 39” mild steel.

Miguel Edwards is an artist who embodies the spirit of living in the West, from its desert environs to the mighty Washington and Oregon outdoors and Northwest coastal cities. Having recently settled in Bend, Oregon, Edwards is a native of New Mexico and identifies with his homeland more than anywhere else. Incidentally, Edwards’ home was close to where Georgia O’Keeffe resided, which may not come as a surprise as his use of shape, form, and line in his sculpture identifies closely with the stark beauty found in this part of the country. Edwards grew up surrounded by many generations of career artists on both sides of his family, which also influenced his art and life as an artist.

“When I lived in Seattle, from 1992 until 2018, I was engrossed in fine art photography, which was very painterly,” describes Edwards. “I photographed many studio nudes, which involved elaborate, large, kinetic sets and body painting with mixing strobes, LEDs, and hot lights to create the atmosphere. Even though photography was my medium, I most identified as being a painter—painting with light—at that point in my career.”

When Edward’s work was published in Billboard Magazine and The Seattle Times, he decided to dive into photography. Edwards worked as a music photographer during Seattle’s music boom, and covered many a promising band. In 2000, Edwards embarked on his first sculpture commission with a friend and then another for Burning Man in 2004, but it was in 2009 when he declared himself a sculptor.

“When I lived in Seattle, from 1992 until 2018, I was engrossed in fine art photography, which was very painterly.”

—Miguel Edwards

Magpie Moon; 68”x 26”x 28” mild steel | Cyclone; 80”x 34”x 24” mild steel | Torsion; 34”x 24”x 56” mild steel

“Seattle in the ‘90s was great,” says Edwards. “I had the last true, standing art studio, at 3,300 square feet, in south Lake Union, now home to Amazon. It was my photography studio—a labyrinth-maze of space set in the hillside that I worked in from 1998 to 2018—but I became a sculptor and needed a better place to do my work.”

Edwards and his wife decided to move to Bend so he could have a shop of his own where he could do his work, especially at the scale he needed. For Edwards, Denver and Southern California are prime markets for his contemporary metal and glass pieces, which he can access in a much more suitable way from Bend. Even though he has done so well as a sculptor, Edwards continues to love his work as a photographer. He says each medium informs the other.

“I’m blessed to have found such a duality with photography and sculpture,” he says. “From taking photographs and crafting images, I have been working with lighting for more than half my life. I also love my sculpture work as well, and it’s nice to have balance between grinding and welding and photography. It’s good for my soul, and it’s great to have good images of my work.”

Edwards describes his art as a combination of influences from his high desert Southwest upbringing and his Northwest coastal urban living with an appreciation for the culture, land, and living in these parts of the country. In Bend, he’s adding and exploring new ideas that have been on his mind. As a member of Oregon’s Central Metal Artist Guild, photographing for Downtown Bend, working with the Bend Design Conference, and being honored as the featured artist for the 2019 Oregon Winterfest in Bend, Edwards is acclimating to his new surroundings with his art and craft well.

“It’s refreshing, rejuvenating, and inspiring to be an artist in Bend,” says Edwards. “There is a really creative community here, which is great because I am very collaborative by nature. I’m often inspired by sharing ideas and exploring ideas with people working in other mediums.”

One of Edwards’ most acclaimed works, Hope Rising, was commissioned for the 50th Anniversary Opening Ceremony of the Special Olympics USA Games in Seattle, Washington. His work emanates a sense of power, but also represents empowerment. His smaller works are more fit for homes and private collections. Using curvy metal arcs, which appear light and wavy, especially when combined with his glass accents, give viewers a sense of weightlessness even though the pieces are very grounded and refined by the limited palette of the flat bar. In addition, the rolled flat bars create an effect, which appears like slices of a covered wall from a photo studio. They change the shape and color depending on how the light hits them. The radius exaggerates the penumbra, which is the transition of light to shadow.

Top: Advena Vasculum; (available) 58”x 18”x 24” mild steel, glass LEDs

Middle: Hope Rising – the Cauldron for the Opening Ceremony of the 50th Anniversary USA Special Olympic Games

Bottom: Perseus II – Permanent installation in Seattle, WA, 35’ tall, kinetic, stainless steel, glass and LEDs

“The arcs are a common part of my work. These pieces relate to my photography and the combining and mixing of light, which creates the gradation and how the arcs play with light—it’s an important part. There’s a feeling of motion, energy, gravity, and light or anti-gravity as well as negative space, which inform my body of work.”

—Miguel Edwards

“It all makes sense and flows,” says Edwards. “I often work on more than one piece at any given time. The joinery and the finishing of a sculpture do take the most amount of time because the joints are so important to the work. The arcs are also a common part of my work because they relate to my photography, revealing the combining and mixing of light, which creates the gradation, and how the arcs play with light—it’s an important part. There’s a feeling of motion, energy, gravity, and light, or anti-gravity, as the pieces visually defy it as well as negative space, which inform my body of work.”

Miguel Edwards is an accomplished sculptor and recognized public artist as well as an editorial and architectural photographer. He has worked with many publications, museums, Fortune 500 companies, and municipalities. His new book, Seattle Art in Public Spaces, is currently available. Visit Miguel Edwards’ work and his creative diversity in action via @themigueledwards on Instagram or migueledwards.com.

Arch Angel Gallery, Palm Springs. Left to Right; Speed Racer 32”x 14”x 15” mild steel, Blue Chase 28”x 14”x 1” mild steel, Eclipse (available) 54”x 36”x 22” mild steel

Terrance Guardipee

Connects the Past, Present, and Future through Ledger Art

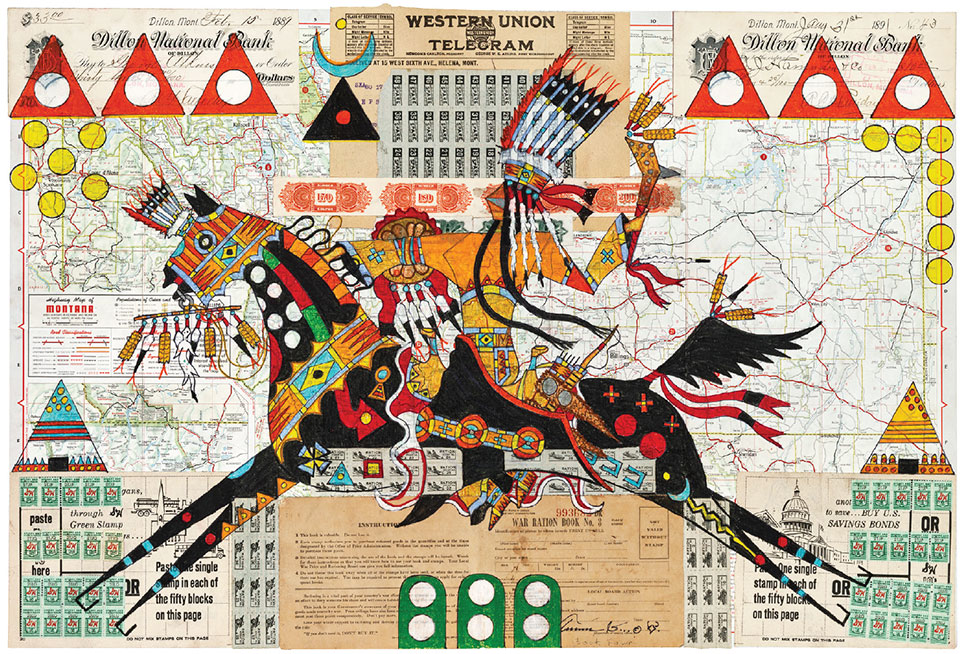

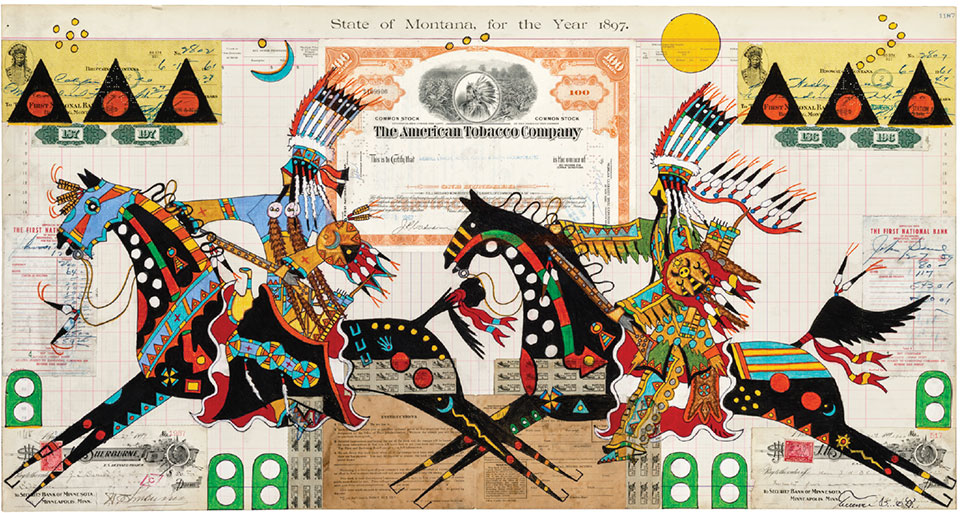

Running Eagle Victory Ride by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, antique Montana map,

antique Montana checks, World War II ration book and stamps, 23” x 18”, October, 2018.

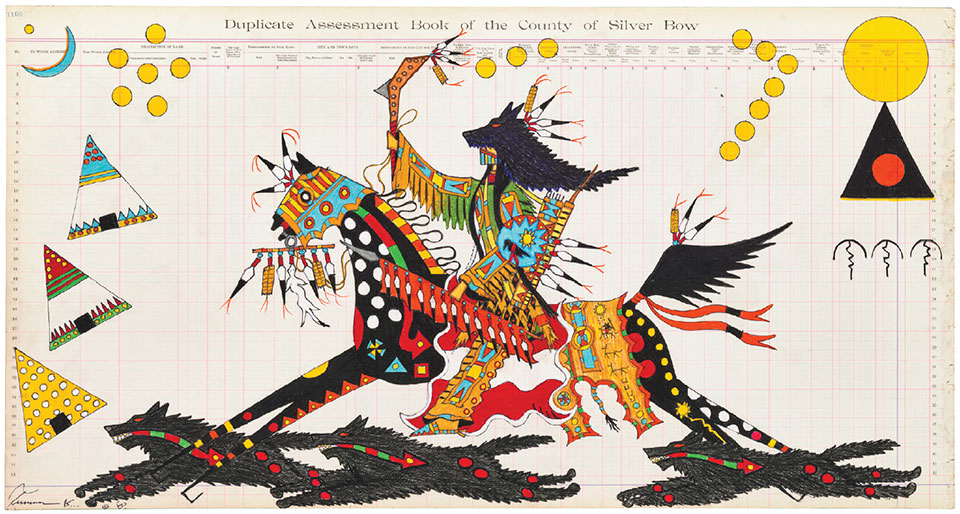

The power of art and its beholder is never so powerful as it is with the work of ledger artist Terrance Guardipee. Guardipee is an internationally acclaimed Blackfeet painter and ledger artist consistently recognized for the traditional depiction of his Blackfeet heritage and contemporary innovation represented through all of his work. He is one of the first Native American artists to revive the historical ledger art tradition, and was the first ledger artist to transform the style from the single-page custom into his signature map collage concept. The map collage concept is based in the ledger art style, but incorporates various antique documents such as maps, war rations, and checks in addition to single-page ledgers.

“It was around 1850, the middle of the 1800s, when the buffalo started to be wiped out,” Guardipee explains. “When the buffalo became scarce, instead of letting our form of pictograph writing or record-keeping die out, we transferred it to paper.” Utilizing antique documents in all of his artwork dating from the mid-19th century, and typically originating from the historical and present Blackfeet homeland of Montana, Guardipee’s work is not only an homage to his ancestors, but it’s also personal to his own family heritage. He adds, “When individual warriors would go into combat, if they lived, they would come home and they would draw what they did in combat.”

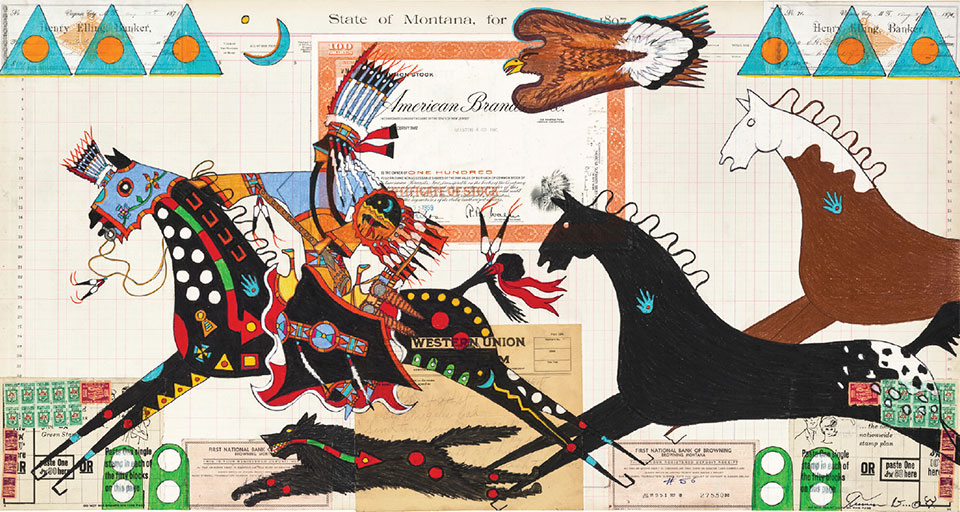

Running Eagle, Blackfeet Warrior Woman War Raid by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, 1897 Montana ledger paper, antique documents, 36” x 19”, September, 2018.

“The ledger paper, antique checks, and documents I use in my artwork are from Montana, which is the ancestral homeland of the Blackfeet (Pikuni) people.”

—Terrance Guardipee

Guardipee is an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Nation of Montana, and illustrates his personal experience of Blackfeet culture in combination with his educational experience in his artwork. Guardipee was raised in the Blackfeet homeland in northern Montana, and as a result, the cultural life and history of the Blackfeet people became a foundational part his identity. Guardipee participates in the traditional Blackfeet ceremonies often depicted in his artwork. His understanding and personal knowledge of authentic Blackfeet history and traditional culture is expressed throughout his work. Guardipee says, “The ledger paper, antique checks, and documents I use in my artwork are from Montana, which is the ancestral homeland of the Blackfeet (Pikuni) people.”

Guardipee lived in Montana until he attended the Institute of American Indian Arts [IAIA] located in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he studied two-dimensional arts. His educational experience at IAIA enabled him to incorporate the contemporary color palette he is known for in a manner that is consistent with Blackfeet tradition.

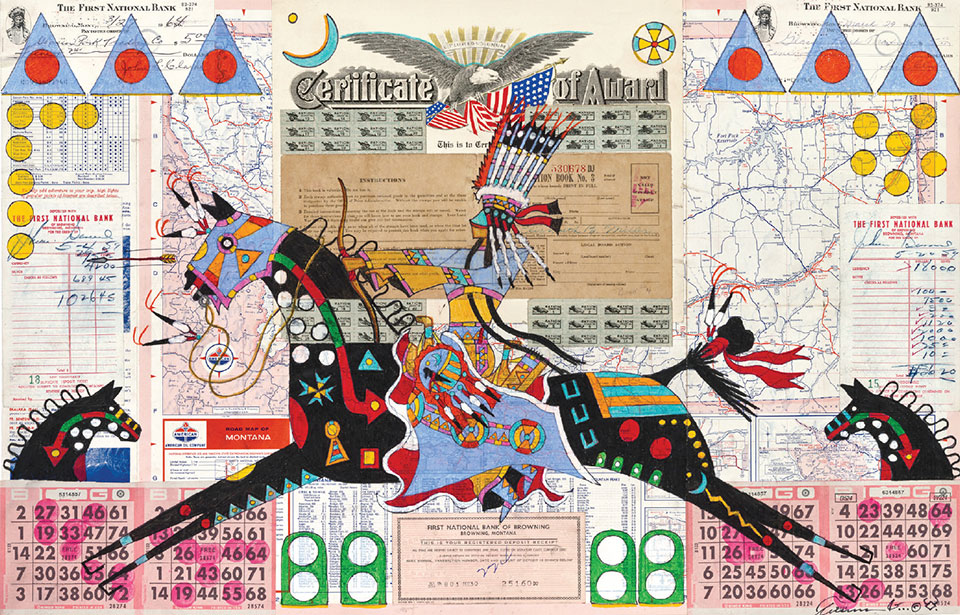

Blue Bird Woman by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, antique Montana map, antique Montana checks, Blackfeet bingo, World War II rations and stamps, 23” x 18”, October, 2018.

“I am so proud to be part of ledger art and its growth and existence into the new millennium.”

—Terrance Guardipee

The innovation Guardipee has demonstrated in his artwork is recognized by numerous museums, prominent Indian art markets, and private collectors.

Through his paintings Guardipee reveals he is, “Showing the change from living in the 1800s… There is a change and evolution with the time. It’s moving forward.”

Running Eagle, Blackfeet Warrior Woman Leader of the Crazy Dog Society by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, 1897 Montana ledger paper, antique Montana documents, World War II ration, 19” x 36”, August, 2018.

Black Wolf, War Medicine by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, 1897 Montana ledger paper, 36” x 19”, September, 2018.

Guardipee is the godfather of ledger art, which he created twenty years ago. His work is featured in the permanent collections of prestigious institutions such as the Smithsonian Institute, the Gene Autry Museum, the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College, and the Museum of Natural History in Hanover, Germany. Furthermore, Guardipee was the featured artist at the National Museum of the American Indian in 2007, and was selected to create an image for The Trail of Painted Ponies at the 2008 50th Anniversary Heard Museum Indian Art Market. Terrance has placed first in ledger art several years in a row at Santa Fe Indian Market, as well as winning best of western art in 2017.

George Gulli

Dreaming of Totems

By Jennifer Walton

When George Gulli sleeps he dreams of totem poles. He contemplates the massive straight larch logs free of their imperfections, center-lined for their design, and cradled upon several sawhorses. He thoughtfully considers the intricate carvings, which could range from traditional Pacific Northwest Coast Native American tribe symbolism to bold and unique designs that he will arrange on the pole to depict his client’s life, environment, or the poles’ site. As a third-generation carver inspired by his father, his larger-than-life totemic art studs the Rocky Mountains, but also lives as far away as Canada and Ireland. For 37 years, his dreams continue to reflect the gratitude he feels bringing this sacred and oft forgotten art to the world.

The history of totemic art depicts many elements, most notably tribal ancestry, individual clans, wealth, status, and legends. Sometimes events or celebrations were told as stories, hence the reference, “Story poles.” The most identifiable totem poles are those from the Northern Pacific Coast, as in Alaska and British Columbia. However, the American Coast Salish tribes in northern Washington play an essential part in the art’s history and its importance in providing interpretation, cultural teachings, and preservation for future generations. Surprisingly, the word totem is not a Northwest Coast Indian term, nor is totem pole whose origination is an Anglo-European term for “monumental wood pillars carved by people of the northern Pacific Coast.” Rather the terms totem and totemism are “anthropological terms that refers to a variety of beliefs and practices concerning relationships between human groups and natural phenomena, usually animals but also plants, celestial bodies, and other living beings, places, and powers of nature… whose idea-typical version is a free-standing, painted, multi-figured pole, often with outstretched wings.”

*Pauline Hillaire, Scalla-Of the Killer Whale, a Lumni cultural historian.

“Today people want art that they can relate to and enjoy, and I want them to know that if they have a special place and want a carving, I’m their guy.”

—George Gulli

So, how did this soft-spoken, wildly intelligent Montanan whose grandfather carved stone in Italian quarries and whose father relished its medium in wood while living in California, take to carving enormous felled trees that require the ultimate in creative visualization to produce a totem so dictated by precision and patience that few non-Natives are ever fully recognized by First Nation tribes as serious artists? By watching his father. “I didn’t want all the knowledge to go away,” says Gulli, “and I began to understand that with each client, and my experience in getting to know them, and the joy they exhibited in having something made specially for them, a piece that looks beautiful in their yard, was really my joy. Being an artist is wonderful. It works for me.” And his clients agree.

There’s the Canadian brewery that ordered an astonishing 24 poles. And, then there’s the couple from Jackson, WY who upon receiving their first work of art a few years back, proudly claimed, “You haven’t heard the last of us yet!” Their recent installation involved a trio of totems whose carving took 10 months. The images on the poles and the sizes of the poles were requested, however the order of the design and details were up to Gulli’s imagination. And, then there’s musician Jason Mraz, whose pole Gulli states combined “a hummingbird on the back of a surfboard, mixed in with an owl, and a cat holding a guitar that I put strings on.” Traditional? No. Whimsical? Possibly, but as Gulli reiterates, “Today people want art that they can relate to and enjoy, and I want them to know that if they have a special place and want a carving, I’m their guy.”

That special place, whether emotional or physical is what Gulli is tempted by. From designing, to measuring, to the pole’s initial cuts, with traditional hand tools like chisels and calipers, to non-traditional tools like grinders and sanders, and chain saws to “chunk out” large pieces of wood, Gulli realizes it is a privilege to carve for that client. “Being able to expand out of my heart is my greatest joy.” That satisfaction is readily seen in both his traditional and non-traditional designs. When a client asks for an eagle or a wolf, Gulli explains its historical significance. The former is known as smart and resourceful as he rules the sky with the ability to transform himself into a human. The latter is very powerful and known to help people who are sick or in need. Totem poles include various symbols that enact powerful reactions to those who stand beneath the monumental sculptures. Alternatively, the poles can signify the entrance to a property, define an honored location, tell a family’s story or a village’s tale, or commemorate special occasions like marriages and anniversaries. Towering overhead, a totem pole is a complex piece of art constructed from a tree that characterizes an idea or statement and when raised is emblematic of a ceremony.

“People blow my mind with their requests. I am always amazed. It makes my heart full.”

—George Gulli

Gulli’s eye for scale and detail is excellent. Working with poles that range in size from 4’ to a staggering 50’, his process is a lesson in restraint and composure. After the carving is complete, selected areas are hand painted prior to sealing the entire pole for protection. Designs from start to finish can range from six weeks to two years depending on size and style. “People blow my mind with their requests. I am always amazed. It makes my heart full.”

To meet Gulli, visit his studio in Victor, MT, where his passion for poles is palpable. Or, visit his website to inquire about the pole you’re dreaming about.