An insider look at artists and galleries

By Sabina Dana Plasse & Jennifer Walton

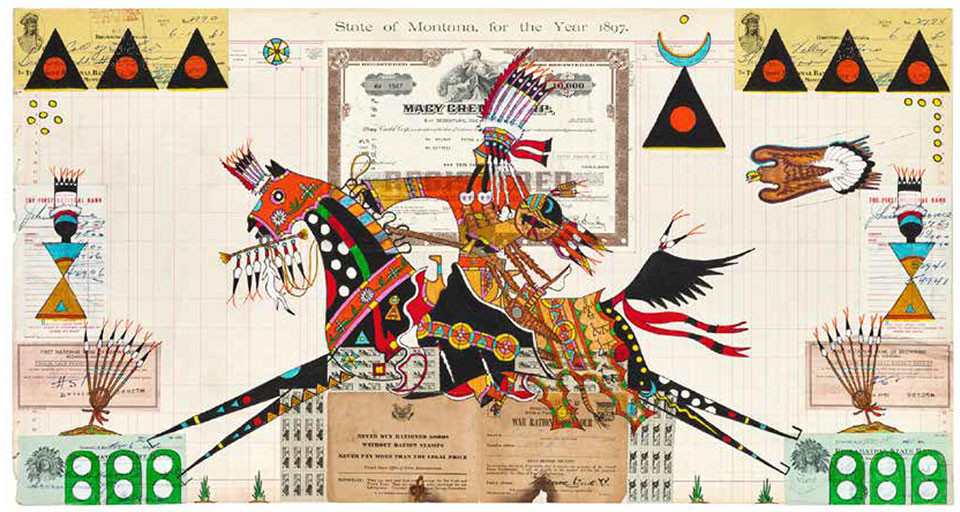

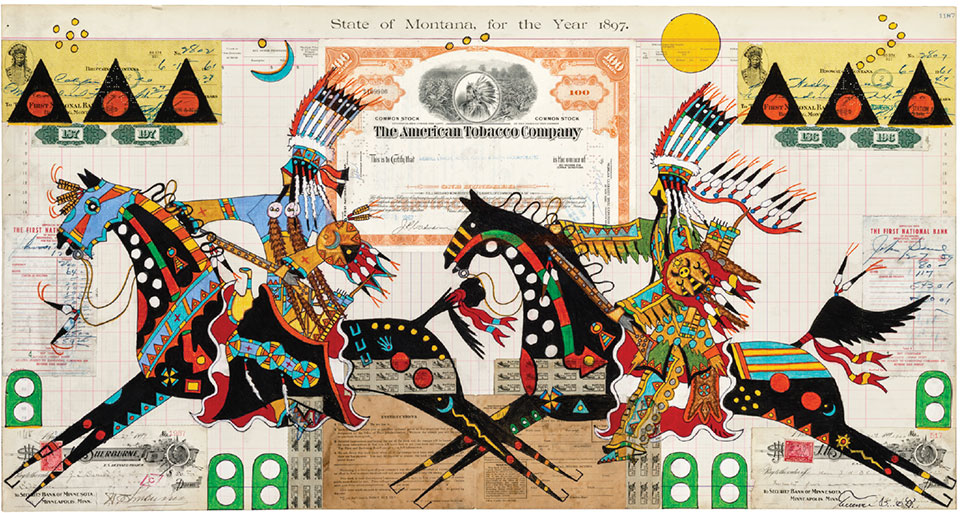

Running Eagle, Blackfeet Warrior Woman by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, 1897 Montana ledger paper, antique Montana checks, antique stock certificate, World War II ration book, and stamps, 36” x 19”, September, 2018.

Jackson Hole’s connection to its Western history can be seen throughout the town. Its appreciation for wildlife, the land, and the culture of the West is important to residents and visitors. However, nothing can be more expressive of the West than the artists, art collectors, and gallery owners who all feel connected to Western heritage, be it past, present, or future. At Fighting Bear, the collection of Native American and Western life antiquities and original artifacts is one-of-a-kind and rare. The authenticity of all the items Fighting Bear presents is a history lesson on its own and worth seeing. From another angle, George Gulli’s craftsmanship in his original totem pole carvings has a unique connection to collectors and art lovers who seek the rare, sublime, or ethereal level of art and heritage. In addition, ledger artist Terrance Guardipee offers his own historic lesson on Native American culture with a look to the future from his ancestral roots. Explore Western fine art throughout this issue of Western Home Journal as another element to discovering or enhancing your dream home and surroundings in the West. As you flip the pages of Western Home Journal, discover your own appreciation for Western heritage and Native American art, influences, and antiquities.

Gros Ventre War Shirt. Buckskin, glass beads, and ermine drops. Circa: 1885

Fighting Bear Antiques

Pulls No Punches for Native American Art

“It’s a large spectrum for Native American art. It’s like anything else; there’s the good, the bad, and the ugly. You have to have a knowledge base to determine what is good and lasting and what is trend. You need to be on the edge of things—not following.”

—Terry Winchell

The name Fighting Bear Antiques begs to tell a story, which owner Terry Winchell explains is his homage to his days as a caretaker on Fish Creek Road when he first arrived in Jackson Hole. “When Hayden surveyed the area in 1878, all the survey maps called Fish Creek Fighting Bear Creek. We tried to get the Forest Service to take back the name Fighting Bear Creek, but to no avail, so I used the name for an LLC I started, and it stuck. It had everything to do with Fish Creek and nothing to do with bears.”

Arapaho Bottom beaded Circa: 1880

Since 1981, Winchell has operated Fighting Bear Antiques in Jackson Hole along with his wife Claudia, where they manage, sell, and collect rare and collectible Thomas Molesworth furnishings, Navajo rugs, pottery, and beadwork as well as other Native American artifacts. Winchell’s passion for authentic Western design, furnishings, and Native American art has evolved since he was a young boy.

Winchell grew up in the West and would accompany his grandfather, an avid fisherman and bird hunter, to Agate Springs Ranch. Winchell and his twin brother would play in the Indian Room at the ranch, which housed authentic Native American artifacts. Winchell developed a fascination for these rarities early on in his childhood, which eventually evolved into his livelihood. “Living in the mountains and seeing all the old ranches with Indian artifacts and deceased Western art, I decided more and more that I wanted my business to gravitate toward this,” says Winchell. “We became more specific and decided to carry more Native American items and Thomas Molesworth furniture, which I wrote a book about, as well as how to help people develop Indian collections. My wife and I, along with a friend, also, wrote a book on Alan Hirschfield’s Indian collection and how to live with Indian art. We delved into the subject and developed wonderful clients. It’s what allows you to grow to have great objects, find things, and buy collections.”

Rare Pitt River Fishing Creel Circa: 1910

Whether it’s Navajo rugs, Native American beadwork, or pottery, the way these items looked in the 1930s is what Winchell is attracted to most and enjoys selling. “Many people collect Native American art as an extension to their art collection,” says Winchell. “A collector may have a Remington or Russell, but as they become more knowledgeable, they will discover more and look for pieces such as Indian beadwork to complement their wall art. It could be a dress, a war shirt, or a shield.”

Becoming an accomplished Native American art collector is a learning process, and it does include contemporary work for some, however Fighting Bear does not sell contemporary works—only artifacts. Winchell adds that there is a great deal happening in Native American art at the museum level, especially in recent times. “Charles and Valerie Diker, who own The Diker Collection, recently gave their collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, which was placed in the American Wing upon their request. This establishes Native American art as its own type of art as it should be.”

Apache Olla (Circa: 1910) on an Old Hickory #627C with Lazy Susan Table, with four chairs, Circa: 1940.

In the background are two Stickley Morris Chairs, and a Tiffany Dragonfly floor lamp.

Necessity and beauty is what Winchell educates his clients and collectors about in Native American art because that is what it meant to the Native Americans who owned and created it. “No different than us, not everyone in the tribe had all good stuff. Those who did, would show it off much like we do,” says Winchell. “I admire contemporary artists and am happy the tradition has continued. After World War I and the Great Depression, Native American art was gone. It didn’t start to re-emerge until the 1960s. Now, there are great artists who exists within the various tribes.”

San Ildefonso Pueblo Black on Red Pot Circa: 1915

“A collector may have a Remington or Russell, but as they become more knowledgeable, they will discover more and look for pieces such as Indian beadwork to complement their wall art.”

—Terry Winchell

Winchell supports his knowledge and interests in Native American art through his voracious appetite for reading and learning about the work, and he will travel with his wife to museum shows for openings so they can admire and participate. In addition, he attends the Indian Market in Santa Fe, and he works with restorers and authenticators. “It’s a large spectrum for Native American art,” Winchell says. “It’s like anything else; there’s the good, the bad, and the ugly. You have to have a knowledge base to determine what is good and lasting and what is trend. You need to be on the edge of things—not following.”

For more information, stop by Fighting Bear Antiques at 375 S Cache St. in Jackson, call 307.733.2669, or visit fightingbear.com.

Thomas Molesworth burled loveseat and two spindle armchairs, with Chimayo weavings. Circa: 1940s

Terrance Guardipee

Connects the Past, Present, and Future through Ledger Art

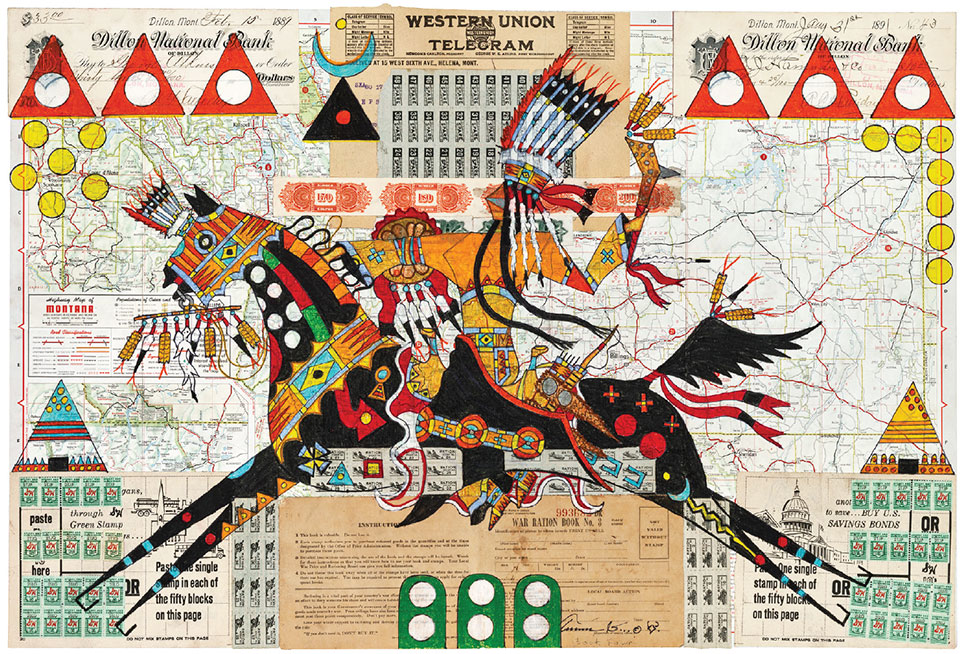

Running Eagle Victory Ride by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, antique Montana map,

antique Montana checks, World War II ration book and stamps, 23” x 18”, October, 2018.

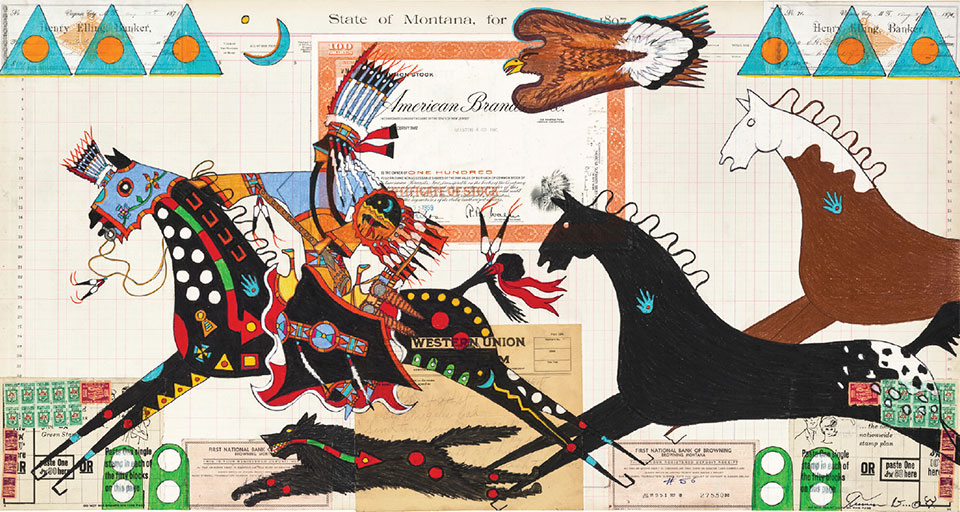

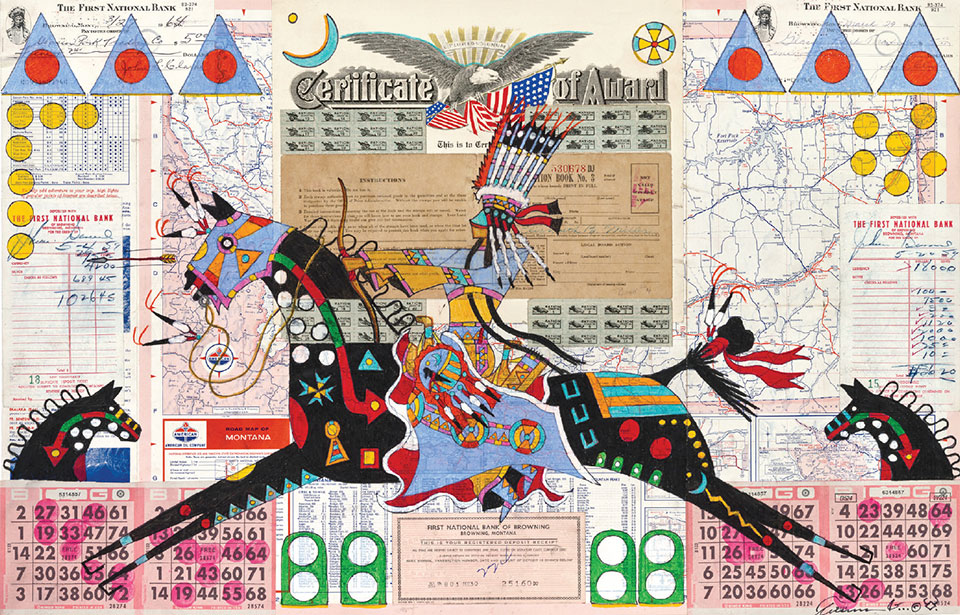

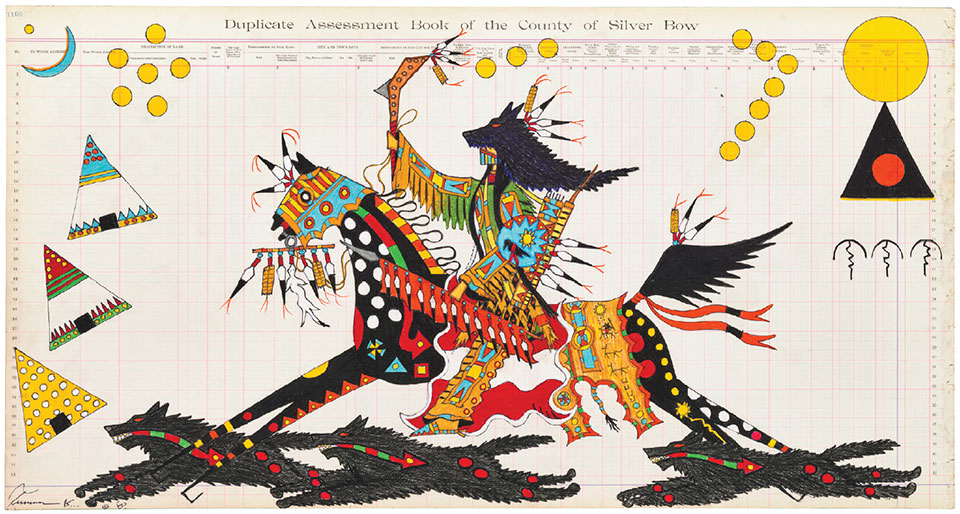

The power of art and its beholder is never so powerful as it is with the work of ledger artist Terrance Guardipee. Guardipee is an internationally acclaimed Blackfeet painter and ledger artist consistently recognized for the traditional depiction of his Blackfeet heritage and contemporary innovation represented through all of his work. He is one of the first Native American artists to revive the historical ledger art tradition, and was the first ledger artist to transform the style from the single-page custom into his signature map collage concept. The map collage concept is based in the ledger art style, but incorporates various antique documents such as maps, war rations, and checks in addition to single-page ledgers.

“It was around 1850, the middle of the 1800s, when the buffalo started to be wiped out,” Guardipee explains. “When the buffalo became scarce, instead of letting our form of pictograph writing or record-keeping die out, we transferred it to paper.” Utilizing antique documents in all of his artwork dating from the mid-19th century, and typically originating from the historical and present Blackfeet homeland of Montana, Guardipee’s work is not only an homage to his ancestors, but it’s also personal to his own family heritage. He adds, “When individual warriors would go into combat, if they lived, they would come home and they would draw what they did in combat.”

Running Eagle, Blackfeet Warrior Woman War Raid by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, 1897 Montana ledger paper, antique documents, 36” x 19”, September, 2018.

“The ledger paper, antique checks, and documents I use in my artwork are from Montana, which is the ancestral homeland of the Blackfeet (Pikuni) people.”

—Terrance Guardipee

Guardipee is an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Nation of Montana, and illustrates his personal experience of Blackfeet culture in combination with his educational experience in his artwork. Guardipee was raised in the Blackfeet homeland in northern Montana, and as a result, the cultural life and history of the Blackfeet people became a foundational part his identity. Guardipee participates in the traditional Blackfeet ceremonies often depicted in his artwork. His understanding and personal knowledge of authentic Blackfeet history and traditional culture is expressed throughout his work. Guardipee says, “The ledger paper, antique checks, and documents I use in my artwork are from Montana, which is the ancestral homeland of the Blackfeet (Pikuni) people.”

Guardipee lived in Montana until he attended the Institute of American Indian Arts [IAIA] located in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he studied two-dimensional arts. His educational experience at IAIA enabled him to incorporate the contemporary color palette he is known for in a manner that is consistent with Blackfeet tradition.

Blue Bird Woman by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, antique Montana map, antique Montana checks, Blackfeet bingo, World War II rations and stamps, 23” x 18”, October, 2018.

“I am so proud to be part of ledger art and its growth and existence into the new millennium.”

—Terrance Guardipee

The innovation Guardipee has demonstrated in his artwork is recognized by numerous museums, prominent Indian art markets, and private collectors.

Through his paintings Guardipee reveals he is, “Showing the change from living in the 1800s… There is a change and evolution with the time. It’s moving forward.”

Running Eagle, Blackfeet Warrior Woman Leader of the Crazy Dog Society by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, 1897 Montana ledger paper, antique Montana documents, World War II ration, 19” x 36”, August, 2018.

Black Wolf, War Medicine by Terrance Guardipee. Oil and pencil, 1897 Montana ledger paper, 36” x 19”, September, 2018.

Guardipee is the godfather of ledger art, which he created twenty years ago. His work is featured in the permanent collections of prestigious institutions such as the Smithsonian Institute, the Gene Autry Museum, the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College, and the Museum of Natural History in Hanover, Germany. Furthermore, Guardipee was the featured artist at the National Museum of the American Indian in 2007, and was selected to create an image for The Trail of Painted Ponies at the 2008 50th Anniversary Heard Museum Indian Art Market. Terrance has placed first in ledger art several years in a row at Santa Fe Indian Market, as well as winning best of western art in 2017.

George Gulli

Dreaming of Totems

By Jennifer Walton

When George Gulli sleeps he dreams of totem poles. He contemplates the massive straight larch logs free of their imperfections, center-lined for their design, and cradled upon several sawhorses. He thoughtfully considers the intricate carvings, which could range from traditional Pacific Northwest Coast Native American tribe symbolism to bold and unique designs that he will arrange on the pole to depict his client’s life, environment, or the poles’ site. As a third-generation carver inspired by his father, his larger-than-life totemic art studs the Rocky Mountains, but also lives as far away as Canada and Ireland. For 37 years, his dreams continue to reflect the gratitude he feels bringing this sacred and oft forgotten art to the world.

The history of totemic art depicts many elements, most notably tribal ancestry, individual clans, wealth, status, and legends. Sometimes events or celebrations were told as stories, hence the reference, “Story poles.” The most identifiable totem poles are those from the Northern Pacific Coast, as in Alaska and British Columbia. However, the American Coast Salish tribes in northern Washington play an essential part in the art’s history and its importance in providing interpretation, cultural teachings, and preservation for future generations. Surprisingly, the word totem is not a Northwest Coast Indian term, nor is totem pole whose origination is an Anglo-European term for “monumental wood pillars carved by people of the northern Pacific Coast.” Rather the terms totem and totemism are “anthropological terms that refers to a variety of beliefs and practices concerning relationships between human groups and natural phenomena, usually animals but also plants, celestial bodies, and other living beings, places, and powers of nature… whose idea-typical version is a free-standing, painted, multi-figured pole, often with outstretched wings.”

*Pauline Hillaire, Scalla-Of the Killer Whale, a Lumni cultural historian.

“Today people want art that they can relate to and enjoy, and I want them to know that if they have a special place and want a carving, I’m their guy.”

—George Gulli

So, how did this soft-spoken, wildly intelligent Montanan whose grandfather carved stone in Italian quarries and whose father relished its medium in wood while living in California, take to carving enormous felled trees that require the ultimate in creative visualization to produce a totem so dictated by precision and patience that few non-Natives are ever fully recognized by First Nation tribes as serious artists? By watching his father. “I didn’t want all the knowledge to go away,” says Gulli, “and I began to understand that with each client, and my experience in getting to know them, and the joy they exhibited in having something made specially for them, a piece that looks beautiful in their yard, was really my joy. Being an artist is wonderful. It works for me.” And his clients agree.

There’s the Canadian brewery that ordered an astonishing 24 poles. And, then there’s the couple from Jackson, WY who upon receiving their first work of art a few years back, proudly claimed, “You haven’t heard the last of us yet!” Their recent installation involved a trio of totems whose carving took 10 months. The images on the poles and the sizes of the poles were requested, however the order of the design and details were up to Gulli’s imagination. And, then there’s musician Jason Mraz, whose pole Gulli states combined “a hummingbird on the back of a surfboard, mixed in with an owl, and a cat holding a guitar that I put strings on.” Traditional? No. Whimsical? Possibly, but as Gulli reiterates, “Today people want art that they can relate to and enjoy, and I want them to know that if they have a special place and want a carving, I’m their guy.”

That special place, whether emotional or physical is what Gulli is tempted by. From designing, to measuring, to the pole’s initial cuts, with traditional hand tools like chisels and calipers, to non-traditional tools like grinders and sanders, and chain saws to “chunk out” large pieces of wood, Gulli realizes it is a privilege to carve for that client. “Being able to expand out of my heart is my greatest joy.” That satisfaction is readily seen in both his traditional and non-traditional designs. When a client asks for an eagle or a wolf, Gulli explains its historical significance. The former is known as smart and resourceful as he rules the sky with the ability to transform himself into a human. The latter is very powerful and known to help people who are sick or in need. Totem poles include various symbols that enact powerful reactions to those who stand beneath the monumental sculptures. Alternatively, the poles can signify the entrance to a property, define an honored location, tell a family’s story or a village’s tale, or commemorate special occasions like marriages and anniversaries. Towering overhead, a totem pole is a complex piece of art constructed from a tree that characterizes an idea or statement and when raised is emblematic of a ceremony.

“People blow my mind with their requests. I am always amazed. It makes my heart full.”

—George Gulli

Gulli’s eye for scale and detail is excellent. Working with poles that range in size from 4’ to a staggering 50’, his process is a lesson in restraint and composure. After the carving is complete, selected areas are hand painted prior to sealing the entire pole for protection. Designs from start to finish can range from six weeks to two years depending on size and style. “People blow my mind with their requests. I am always amazed. It makes my heart full.”

To meet Gulli, visit his studio in Victor, MT, where his passion for poles is palpable. Or, visit his website to inquire about the pole you’re dreaming about.